2013 Study Foudn That Doulas Were Less Likely to Deliver Babies With Low Birth Weight

Abstract

Introduction Although home-visiting programs typically appoint families during pregnancy, few studies have examined maternal and child health outcomes during the antenatal and newborn period and fewer take demonstrated intervention impacts. Illinois has developed an innovative model in which programs utilizing evidence-based home-visiting models contain community doulas who focus on childbirth education, breastfeeding, pregnancy wellness, and newborn care. This randomized controlled trial (RCT) examines the impact of doula-dwelling-visiting on birth outcomes, postpartum maternal and baby wellness, and newborn care practices. Methods 312 young (Thousand = 18.4 years), meaning women across four communities were randomly assigned to receive doula-home-visiting services or case management. Women were African American (45%), Latina (38%), white (8%), and multiracial/other (nine%). They were interviewed during pregnancy and at iii-weeks and three-months postpartum. Results Intervention-group mothers were more probable to attend childbirth-preparation classes (50 vs. 10%, OR = 9.82, p < .01), but at that place were no differences on Caesarean delivery, birthweight, prematurity, or postpartum depression. Intervention-grouping mothers were less likely to use epidural/pain medication during labor (72 vs. 83%; OR = 0.49, p < .01) and more likely to initiate breastfeeding (81 vs. 74%; OR = 1.72, p < .05), although the breastfeeding affect was not sustained over fourth dimension. Intervention-group mothers were more likely to put infants on their backs to sleep (seventy vs. 61%; OR = ane.64, p < .05) and utilise car-seats at three weeks (97 vs. 93%; OR = 3.16, p < .05). Conclusions for practices The doula-home-visiting intervention was associated with positive babe-care behaviors. Since few bear witness-based home-visiting programs accept shown health impacts in the postpartum months after nativity, incorporating doula services may confer additional health benefits to families.

Significance

What's Known on This Subject Research has shown that home-visiting programs accept positive impacts in varied domains of parent and kid functioning. However, few studies have examined maternal and child health at birth and during the newborn menstruum.

What This Study Adds This report, evaluating a home-visiting model that incorporates customs doulas into the intervention team, demonstrates improvements in childbirth preparation, breastfeeding initiation, safe sleep practices, and early car-seat use. The intervention was associated with less use of pharmacologic pain control during labor, but not with other indicators of female parent and newborn wellness at birth or improvements in maternal depression.

Introduction

Dwelling Visiting and Maternal Child Health

Growing evidence shows that babyhood habitation-visiting programs for socially and economically vulnerable families can have impacts in multiple areas, including maternal and child health, parenting, child evolution, and family economic cocky-sufficiency (Paulsell et al. 2010). When federal back up for dwelling visiting was dramatically increased in 2010 through the Maternal Baby Early Babyhood Home Visiting (MIECHV) program (Thompson et al. 2011), the legislation set expectations that plan should have impacts across multiple domains, including "improved maternal and newborn health" ("Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act"). Although MIECHV legislation did non prioritize specific maternal and newborn health outcomes, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services' national wellness pattern, Healthy People 2020 (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion 2014), identifies such priorities: mother health at nascence and postpartum (including omnipresence at childbirth training classes, reduction in Caesarean deliveries, reduction in maternal postnatal medical complications, and reduced postpartum low), infant morbidity and mortality (including reduction in infant deaths, low birthweight and preterm birth), and infant care (including increased breastfeeding and increased proportion of infants put to sleep on their backs).

The The states lags behind other developed nations with respect to infant mortality and low birthweight (MacDorman et al. 2014; Wardlaw 2004), and there are disparities in newborn and pregnancy outcomes related to maternal age, poverty and race (Bryant et al. 2010; Martin et al. 2017; Nagahawatte and Goldenberg 2008). Despite evidence that breastfeeding has advantages for mother and child health (Stuebe 2009), breastfeeding rates remain depression in the United states of america among young, low-income and African-American women (McDowell et al. 2008). Additionally, although the American Academy of Pediatrics (Task Force on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome 2016) recommends that infants be placed in supine sleep positions in their own beds in order to reduce the risk of sleep-related infant deaths, infants born to young, low-income mothers accept a relatively high hazard for prone placement and for co-sleeping (Colson et al. 2009; Caraballo et al. 2016).

Despite many studies on babe and early on babyhood home visiting, few reports document impacts on maternal and newborn health or newborn care practices. Just a few home-visiting studies have examined maternal depression during the showtime postpartum months, and none accept institute programme impacts reducing symptoms (eastward.g., Barlow et al. 2013; Carta et al. 2013). A few studies have shown impacts on preventing low birthweight and/or preterm birth (Lee et al. 2009; Williams et al. 2017), but others have not (e.yard., Kitzman et al. 1997; Olds et al. 1986). Nigh studies have non examined newborn health. Some habitation-visiting studies have reported impacts on early breastfeeding (Kitzman et al. 1997; Wen et al. 2011), but most have not found impacts (Green et al. 2014; Kemp et al. 2013; Mitchell-Herzfeld et al. 2005).

Customs Doulas

Twenty years ago, early on childhood advocates in Illinois were concerned about home-visiting programs having limited impact on maternal and newborn health outcomes. A partnership betwixt the Irving Harris Foundation, HealthConnect One and the Ounce of Prevention Fund developed a model where doulas were integrated into home-visiting programs in guild to heighten the quality of wellness-related services during pregnancy and the postnatal flow (Glink 1998, 1999).

In the "community doula" model that resulted, doulas are customs health workers who have training in pregnancy health, childbirth grooming, labor back up, lactation counseling, and newborn care. They serve as specialized dwelling house visitors, providing dwelling-based education and back up during the concluding one-half of pregnancy and for half dozen weeks postpartum. Doulas accompany laboring women to the hospital to provide comfort measures and emotional back up and to offer postpartum aid around breastfeeding and bonding.

The rationale for including doulas within a home-based model drew from strong meta-analytic testify that doula labor support is associated with improved health outcomes, including fewer Caesarean deliveries, decreased employ of analgesia/anesthesia, shorter labors, and college Apgar scores (Hodnett et al. 2013). One RCT examining the bear upon of a community doula model in which doulas provided home visits in addition to labor back up constitute increases in breastfeeding initiation among young, low-income mothers (Edwards et al. 2013).

The goal of this RCT is to examine whether young, depression-income families receiving doula-dwelling house-visiting services, compared to families receiving lower-intensity case-management services, have improved maternal and kid health outcomes during the period between birth and 3 months of age.

Methods

Study Sites, Enrollment, Randomization and Follow-Up Procedures

Study recruitment took identify between 2011 and 2015. Partners in the RCT were four agencies offering doula-dwelling-visiting programs to young mothers in loftier-poverty Illinois communities. Two programs were located in a large urban center, and two in smaller urban areas. 1 served an African-American population, one served a Latinx population, and two served mixed-ethnic populations. Programs serving Latinx populations provided services in English and Spanish. Each of the programs already was implementing an evidence-based home visiting model (see overview of evidence in Paulsell et al. 2010), either Good for you Families America (HFA) ("Good for you Families America" 2015) or Parents as Teachers (PAT) ("Parents equally Teachers" 2018). Programs were from a network of state-funded home-visiting programs and not demonstration programs for enquiry purposes only.

Programs received information about young pregnant women from their usual referral networks—public health departments, WIC programs, health clinics, and schools. Program staff contacted women to determine eligibility and explain the program and research study. Women were told that the only fashion to participate in the doula-domicile-visiting program was to participate in the study. If they were non interested in the research, they received contact data for other customs programs providing services for pregnant women, including case management, home visiting, and parenting programs in hospitals and health clinics. To be eligible for the study, women needed to exist under 26, less than 34 weeks gestation, living in the program geographic catchment area, planning to remain the expanse, and meeting sociodemographic risk criteria used by the HFA or PAT models. Out of ethical concerns, meaning women who were under 14, involved with the child welfare or juvenile justice systems, or had meaning cognitive impairments were excluded from the report and offered home-visiting services.

After screening, the enquiry squad scheduled a baseline session with mothers that included a written-informed-consent procedure and a 2-h structured interview. At the terminate of this session, the interviewer opened a sealed opaque envelope that showed whether the participant was assigned to doula-home-visiting services (intervention condition) or case management (control condition). These envelopes had been prepared by the principal investigator earlier the outset of the written report. Randomization tables were created separately for each customs.

At 37-weeks of pregnancy, 3-weeks postpartum and iii-months postpartum, mothers were re-interviewed. Families received modest budgetary bounty at each session and a baby book and toy at each postpartum session. All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at The University of Chicago, and the study is registered with clinicaltrials.gov [identifier NCT01947244].

Description of Group Conditions

Doula-Dwelling house-Visiting Intervention

Later randomization to the intervention group, doula-habitation-visiting programs assigned families a home visitor (also chosen a Family Support Worker or Parent Educator) and a customs doula. Doulas and home visitors all had deep roots in their communities. All home visitors and doulas had completed at to the lowest degree the foundational grooming required by their national models, and doulas had completed at least the bones training provided through the Ounce of Prevention Fund. During pregnancy and postpartum, mothers were visited weekly by a home visitor, doula, or both together. The doula worked with the mother more intensively during pregnancy and the first weeks postpartum, while the habitation visitor became the chief provider by six weeks postpartum.

Home visitors focused on the mother-infant relationship, child development, child safety, and educational-work planning, also as screening to make sure that family unit basic needs were being met. Doulas focused on bug related to pregnancy health, childbirth training, breastfeeding, newborn care, postpartum health, and early bonding. Doulas sometimes accompanied mothers to prenatal and postpartum medical visits. Doulas attended births at the hospital where they provided mothers with physical comfort, emotional support, and advocacy during labor and commitment and breastfeeding counseling postpartum. Doulas also offered prenatal classes at the programme sites. All programs conducted regular depression screenings and made referrals to mental health consultants.

Case Management Control

After randomization to the control group, mothers were provided information about instance management services in their communities, and case management providers were given mothers' contact information. In some communities, mothers were referred to existing state-funded case-direction providers; in other communities, social-service providers were contracted to provide case management. It was expected that mothers would have at least two meetings with instance managers—one during pregnancy and one after nascence. Meetings could be in families' homes, in agency offices, or occasionally by phone. Case managers determined whether families' basic needs with respect to wellness, housing, food, employment, education, and childcare were beingness met, and if needed, made referrals. Case managers screened to identify needs for services regarding substance misuse, depression, and domestic violence.

Interviews

Outcomes were called based on Healthy People 2020 maternal and newborn health priorities and outcomes that have been reported in previous studies of doula interventions. Interviews were available in English language and Spanish and administered in the mother'southward preferred linguistic communication. Interviewers working in Latinx communities were bilingual. Interviews were usually conducted in families' homes.

At baseline, interviewers asked questions related to the pregnancy, health care, mental health, didactics and employment, and relationships with family. Baseline interview questions were used to check equivalence of the groups as randomized.

At all follow-upwardly interviews, intervention-grouping mothers were asked well-nigh numbers of contacts with doulas and habitation visitors. All mothers were asked almost childbirth preparation class omnipresence and any other pregnancy/parenting services.

At the 3-week postpartum interview (or 3-calendar month interview if mother missed the before session), mothers reported on nascence outcomes, including pain medication/epidural use during labor, vaginal versus Caesarean commitment, gestational age (GA) at delivery, infant birthweight, NICU admission, length of hospital stay, and mother and/or newborn re-hospitalizations.

At the 3-week and 3-calendar month interviews, mothers reported on breastfeeding. Breastfeeding initiation was defined as breastfeeding at to the lowest degree through the hospital stay. Mothers were asked how oftentimes they used a automobile-seat, the positions they used when laying down their babe to slumber and where the infant slept. Mothers reported on depressive symptoms using the Centre for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Calibration (CES-D) (Radloff 1977), dichotomized to identify mothers with clinically significant levels of depression (≥ 16).

Analytic Plan

First, the intervention and control groups were compared on multiple baseline maternal characteristics measured before randomization using t-tests and Chi foursquare tests to check whether randomization was successful. Second, intent-to-treat logistic regression analyses were conducted to examine the bear upon of the doula-home-visiting intervention on outcomes measured at 37-weeks pregnancy, 3-week postpartum, and iii-months postpartum. Odds ratios, 95% confidence intervals, and ane-tailed p-values were calculated for each upshot, using the control group as the reference grouping. Program site was used as a covariate in all analyses, and whatsoever baseline maternal variables that differed between the two groups were used as covariates.

Results

Sample Characteristics

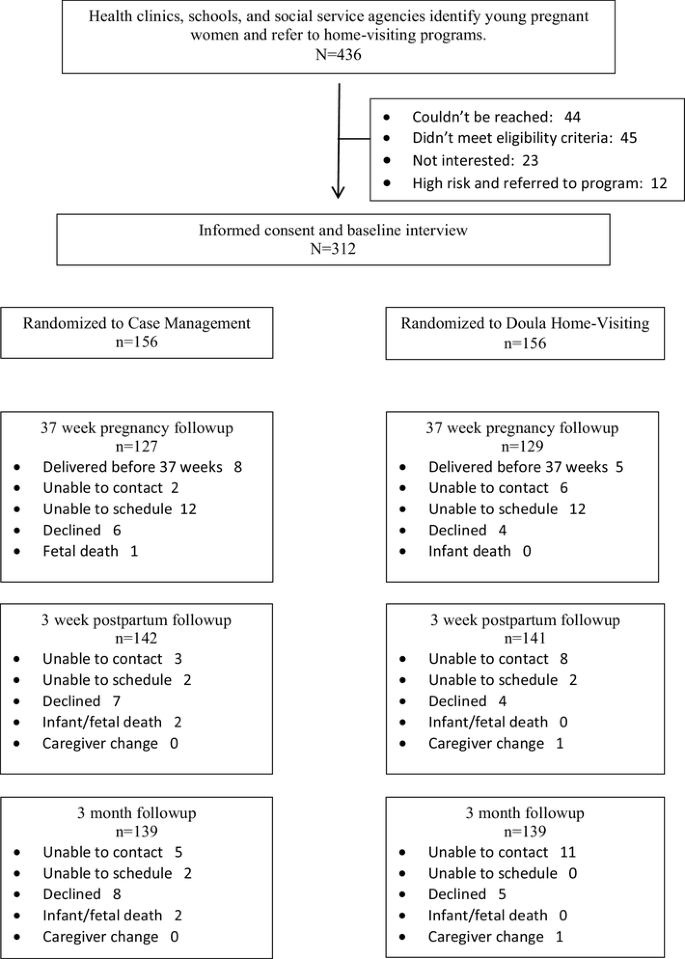

Altogether 436 women were referred to the programs. 312 were enrolled in the sample and randomly assigned to the two conditions. Reasons families were not enrolled included inability to contact, women non wanting to participate in services or the study, women non coming together eligibility criteria, and women at high risk and referred to program services without randomization.

Interviews were completed for 256 mothers (82%) at 37-weeks of pregnancy, 283 mothers (91%) at three-weeks and 278 mothers (89%) at 3-months. Sample attrition was unrelated to program site, race/ethnicity, historic period, education, co-residence, or prenatal depressive symptoms. There were no differences in sample compunction at either follow-up interview betwixt the intervention and control groups. Figure 1 is a Consort nautical chart identifying the flow of subjects through the study.

Study Consort diagram

Participants in the baseline interview were young and low-income, with well-nigh half identifying equally black/African American (45%, northward = 140) and but over a third Latina/Hispanic (38%, n = 117). 11% of mothers preferred to be interviewed in Spanish. Virtually mothers were in their 2nd trimester of pregnancy and expecting their first kid. Over 2-thirds were partnered (coupled, engaged, married) with the father of the baby (71%, n = 220). Table ane shows that the only baseline difference betwixt groups was that more intervention-grouping mothers were living with a parent effigy compared to control-grouping mothers (77 vs. 64%, p < .05). Co-residence with parent figure was a control variable in all analyses.

Intervention Participation

Near all mothers (99%, northward = 153) assigned to the doula-home-visiting group received at least one dwelling visit. Amidst mothers interviewed at 37 weeks, the average number of doula visits prior to 37 weeks was 8.ix (SD = 6.9) and the boilerplate number of visits from a home company was 5.8 (SD = iv.viii). Doulas were present in the infirmary for 75% (n = 106) of the births. Past 3-months postpartum, 131 (92%) mothers had received at least 1 postpartum visit from their doula and 120 (84%) had received at least 1 postpartum visit from their home visitor.

Intervention Effects

Mother Birth and Postpartum Health

Results from logistic regression analyses using ane-tailed hypothesis tests (Tabular array 2) show that intervention-group mothers were more probable to nourish a childbirth education class during pregnancy (OR 9.82, 95% CI 4.84–19.89) and less likely to use epidural or other pain medication during labor compared to control-grouping mothers (OR 0.47, 95% CI 0.25–0.88). The intervention was not associated with Caesarean deliveries, mother re-hospitalizations, or female parent postpartum depressive symptoms.

Infant Mortality and Morbidity

The intervention was not associated with preterm births (GA < 37 weeks), depression birthweight, NICU admission, length of newborn hospital stay, re-hospitalization of infants, having a pediatrician or pediatric clinic at 3 weeks, or having a well-infant bank check upwardly by 3 months. Most all families in both groups reported having a pediatrician for their infants (98%), and all mothers reported taking their infant in for at to the lowest degree 1 well-baby check up by three months of age.

Newborn Intendance Practices

Mothers in the intervention group were more than probable to initiate breastfeeding in the hospital (OR ane.67, 95% CI 0.91–3.03). At 3 weeks, mothers in the intervention group were more probable to always identify their infants on their backs for sleeping (OR 1.64, 95% CI 0.97–2.77) and to ever put their infants in a motorcar seat when traveling by car (OR iii.67, 95% CI 1.06–12.70). In that location was a not-statistically-significant trend for infants in the intervention group to have their ain beds (OR 1.44, 95% CI 0.89–2.34, p = .07). At that place were no group differences on breastfeeding, sleeping or auto seat utilise at three months.

Discussion

Although well-nigh early-childhood home-visiting programs begin working with families during pregnancy or shortly later nativity, relatively few evaluations have examined maternal and child wellness outcomes at birth or during the newborn period. The doula-home-visiting model, in which a community doula partners with a home company during pregnancy and through vi-weeks postpartum, provides greater accent on pregnancy health, childbirth, breastfeeding, and newborn health than most other dwelling house-visiting models, and additionally, offers hospital-based support during childbirth and agency-based childbirth grooming classes. This RCT shows that the doula-dwelling-visiting intervention has impacts on childbirth preparation, epidural/pain medication use during labor, breastfeeding, and safe newborn-care practices.

Mothers receiving the intervention were more likely to have attended a childbirth preparation class. Although virtually all mothers in the sample had opportunities to nourish childbirth classes through prenatal clinics and hospitals, few control-group women took advantage of such opportunities. Half of the women in the intervention group participated in such classes either at clinics and hospitals or through weekly classes offered by their home-visiting programs. Moreover, all mothers who were visited by a doula also received individualized childbirth pedagogy at home. Perhaps equally a issue of this preparation and the presence of the doula during labor, mothers in the intervention grouping were less likely to utilise pharmacologic pain relief during labor, a finding similar to other studies of doula labor support (Hodnett et al. 2013). Yet, as with the few other dwelling house-visiting studies examining birth outcomes, in that location were no intervention impacts on Caesarean deliveries, depression birthweight, or preterm birth. Although other studies of labor-but doulas have found reductions of Caesarean rates (Hodnett et al. 2013), most of these studies limited samples to obstetrically low-risk mothers whose labors began spontaneously. The present sample of young, depression-income mothers was likely more than medically circuitous.

Mothers in the intervention were more likely to initiate breastfeeding, consistent with previous research on community doulas (Edwards et al. 2013). Few other home-visiting studies have plant impacts on breastfeeding. Doulas, by offering skilled lactation counseling throughout pregnancy in mothers' homes and postpartum in the hospital, increase breastfeeding initiation, even among populations that have traditionally low breastfeeding rates. However, the intervention touch on on breastfeeding was not sustained, and only about 20% of mothers were breastfeeding at three months. Research is needed to sympathize why many mothers initiated breastfeeding but discontinued chop-chop postpartum (east.g., Rozga et al. 2015) and what strategies might exist effective for supporting young mothers during that disquisitional time. Notwithstanding, fifty-fifty brief periods of breastfeeding may have health benefits to infants by style of colostrum (e.chiliad., Bardanzellu et al. 2017).

The doula-domicile-visiting intervention did non show impacts on postpartum maternal depressive symptoms, consistent with findings from nigh other habitation-visiting evaluations. Postpartum depression is powerfully influenced past a complex gear up of biological factors, chronic stress, trauma history, and instability in relationships with infants' fathers and accept been challenging to preclude (Edwards et al. 2012; Grote et al. 2011). A systematic review constitute evidence that home-based services take the potential to be effective in preventing postpartum depression, only to date testify is express to intensive interventions delivered past professionals (Dennis and Dowswell 2013).

Mothers in the intervention were more likely to e'er place their newborns on their backs to slumber and always use a motorcar-seat. Few previous abode-visiting studies take looked at early infant safety practices. Although the present study does non accost the manner in which mothers received these safe messages, previous research suggests that low-income mothers may reject infant slumber recommendations, for instance, because of distrust of wellness professionals, reliance on advice from family unit members, and concern for baby comfort (Colson et al. 2005). Doulas have many opportunities during prenatal visits and through their intimate care during labor to get trusted advisors to young mothers. By being present in the hospital and the dwelling house during the primeval weeks when mothers get-go establish sleep exercise, doulas may have unique opportunities to explain to mothers and other family unit members the benefits of safe slumber practices and to offer mothers strategies for soothing babies who seem uncomfortable on their backs.

Notably, although doula-home-visiting impacts on newborn care practices were institute in the first weeks postpartum, group differences diminished by 3 months. It may be that over time families chose babe feeding or sleeping practices they felt were most effective for their family circumstances or babe preferences. Information technology may be that as home visitors took over intervention piece of work from the doulas, the focus of the piece of work shifted from feeding and sleep practices to other important areas such as responsive parenting, kid evolution, and female parent's personal development.

Finally, although the nowadays study has many methodological strengths—a randomized pattern implemented within programs taken to calibration in real agency settings, it also has limitations. The sample drew from just four programs in a unmarried state and excluded adolescents at the virtually farthermost levels of risk. Because information in this paper were provided through mother report and not administrative records, reliable information on important medical procedures and outcomes during labor, such every bit qualifications of wellness providers and Apgar scores, were unavailable. Because each mother in the intervention group was offered services from a doula and habitation visitor squad, the independent contribution of the two dissimilar providers could not be determined. The sample was underpowered to detect important, but relatively rare maternal and kid health problems, particularly infant mortality. Nevertheless, the study identified impacts on important maternal and newborn health outcomes that accept rarely or never been plant in other evaluations of home-visiting models. Future research should focus on a broader set of health outcomes, including outcomes documented through administrative records, and examine the processes through which doulas convey health data, contrasting their part to abode visitors who are non doulas.

Consequent with an already potent evidence base regarding birth doula interventions and a smaller body of work on community doulas, the present study shows improved maternal and child health when mothers have admission to doula services through community-based home-visiting programs. Nonetheless, in that location are before long funding barriers to increasing depression-income women's access to doula services. Simple steps to improving admission would be for states to recognize customs doula services every bit bear witness-based interventions eligible for existing dwelling house-visiting funding, equally has been the example in Illinois, and too to develop state certification processes and other mechanisms for using Medicaid funds to reimburse for doula services, every bit has happened in Oregon and Minnesota (Gay 2016; Kozhimannil et al. 2014).

Change history

-

20 August 2018

The article "Randomized Controlled Trial of Doula-Home-Visiting Services: Impact on Maternal and Infant Health", written past Sydney L. Hans, Renee C. Edwards and Yudong Zhang, was originally published electronically on the publisher's cyberspace portal (currently SpringerLink) on 31 May 2018 without open admission. With the writer(southward)' decision to opt for Open up Option the copyright of the article changed on xviii July 2018 to © The Author(s) 2018 and the article is forthwith distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution four.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/iv.0/), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long every bit yous give appropriate credit to the original writer(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were fabricated.

References

-

Bardanzellu, F., Fanos, Five., & Reali, A. (2017). "Omics" in human colustrum and mature milk: Looking to old data with new eyes. Nutrients, 9, 843.

-

Barlow, A., Mullany, B., Neault, N., Compton, S., Carter, A., Hastings, R., … Walkup, J. T. (2013). Effect of a paraprofessional dwelling house-visiting intervention on American Indian teen mothers' and infants' behavioral risks: A randomized controlled trial. American Periodical of Psychiatry, 170(one), 83–93.

-

Bryant, A. S., Worjoloh, A., Caughey, A. B., & Washington, A. Eastward. (2010). Racial/ethnic disparities in obstetric outcomes and care: Prevalence and determinants. American Periodical of Obstetrics & Gynecology, 202(4), 335–343.

-

Caraballo, K., Shimasaki, S., Johnston, M., Tung, G., Albright, K., & Halbower, A. C. (2016). Knowledge, attitudes, and chance for sudden unexpected infant decease in children of boyish mothers: A qualitative study. Journal of Pediatrics, 174, 78–83.

-

Carta, J. J., Lefever, J. B., Bigelow, K., Borkowski, J., & Warren, S. F. (2013). Randomized trial of a cellular phone-enhanced home visitation parenting intervention. Pediatrics, 132(Supplement 2), S167–S173.

-

Colson, E. R., McCabe, L. K., Fob, Grand., Levenson, Due south., Colton, T., Lister, Yard., … Corwin, Thousand. J. (2005). Barriers to following the back-to-sleep recommendations: Insights from focus groups with inner-city caregivers. Ambulatory Pediatrics, v(6), 349–354.

-

Colson, E. R., Rybin, D., Smith, L. A., Colton, T., Lister, G., & Corwin, Chiliad. J. (2009). Trends and factors associated with infant sleeping position: The National Infant Sleep Position Study, 1993–2007. Athenaeum of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 163(12), 1122–1128.

-

Dennis, C.-L., & Dowswell, T. (2013). Psychosocial and psychological interventions for preventing postpartum depression. Cochrane Database of Systemic Reviews, two, CD001134.

-

Edwards, R. C., Thullen, M. J., Isarowong, North., Shiu, C.-S., Henson, L., & Hans, S. L. (2012). Supportive relationships and the trajectory of depressive symptoms among immature, Afrian American mothers. Journal of Family Psychology, 26(3), 585–594.

-

Edwards, R. C., Thullen, M. J., Korfmacher, J., Lantos, J. D., Henson, L. K., & Hans, Southward. Fifty. (2013). Breastfeeding and complementary nutrient: Randomized trial of customs doula home visiting. Pediatrics, 132, S160-S166.

-

Gay, East. D. (2016). Insurance coverage of doula care would benefit patients and service providers alike. Rewire. Retrieved May 28, 2018, from https://rewire.news/commodity/2016/01/14/insurance-coverage-doula-intendance-do good-patients-service-providers-alike/.

-

Glink, P. (1998). The Chicago Doula Project: A collaborative endeavour in perinatal support for birthing teens. Nix to Three, xviii, 44–fifty.

-

Glink, P. (1999). Engaging, educating, and empowering young mothers: The Chicago Doula Project. Zero to Iii, 20, 41–44.

-

Light-green, B. 50., Tarte, J. M., Harrison, P. M., Nygren, M., & Sanders, Thousand. B. (2014). Results from a randomized trial of the Healthy Families Oregon accredited statewide plan: Early program impacts on parenting. Children and Youth Services Review, 44, 288–298.

-

Grote, Due north. K., Bledsoe, Southward. E., Wellman, J., & Chocolate-brown, C. (2011). Depression in African American and White women with low incomes: The role of chronic stress. In L. E. Davis (Ed.), Racial disparity in mental health services: Why race still matters. Philadelphia, PA: Haworth Press.

-

Salubrious Families America. (2015). Retrieved May 28, 2018, from http://www.healthyfamiliesamerica.org.

-

Hodnett, East. D., Gates, South., Hofmeyr, 1000. J., & Sakala, C. (2013). Continuous support for women during childbirth. Cochrane Library, Issue seven.

-

Kemp, L., Harris, E., McMahon, C., Matthey, S., Vimpani, M., Anderson, T., … Aslam, H. (2013). Benefits of psychosocial intervention and continuity of care past child and family health nurses in the pre and postnatal period: process evaluation. Journal of Avant-garde Nursing, 69(viii), 1850–1861.

-

Kitzman, H., Olds, D. L., Henderson, J., Hanks, C. R., Cole, C., Tatelbaum, R. R., et al (1997). Upshot of prenatal and infancy home visitation past nurses on pregnancy outcomes, childhood injuries, and repeated childbearing: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 278, 644–652.

-

Kozhimannil, Thou. B., Attanasio, L. B., Jou, J., Joarnt, Fifty. K., Johnson, P. J., & Gjerdingen, D. Yard. (2014). Potential benefits of increased access to doula support during childbirth. American Periodical of Managed Care, twenty(8), e111–e121.

-

Lee, Due east., Mitchell-Herzfeld, S., Lowenfels, A. A., Greene, R., Dorabawila, Five., & DuMont, K. A. (2009). Reducing low birth weight through habitation visitation: A randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 36(2), 154–160.

-

MacDorman, M. F., Matthews, T., Mohangoo, A. D., & Zeitlin, J. (2014). International comparisons of infant mortality and related factors: Usa and Europe 2010. National vital statistics reports: from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 63(5), i–7.

-

Martin, J. A., Hamilton, B. E., Osterman, M. J., Driscoll, A. K., & Mathews, T. J. (2017). Births: Final Data for 2015. National vital statistics reports: From the Centers for Disease Command and Prevention. National Eye for Wellness Statistics, National Vital Statistics Arrangement, 66(1), one.

-

McDowell, N. K., Wang, C. Y., & Kennedy-Stephenson, J. (2008). Breastfeeding in the The states: Findings from the national health and nutrition examination surveys, 1999–2006. NCHS Data Cursory, v, 1–eight.

-

Mitchell-Herzfeld, Southward., Izzo, C., Greene, R., Lee, Due east., & Lowenfels, A. (2005). Evaluation of Salubrious Families New York (HFNY): Showtime year program impacts. New York State Albany: Part of Children and Family unit Services Bureau.

-

Nagahawatte, N. T., & Goldenberg, R. L. (2008). Poverty, maternal wellness, and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1136, 80–85.

-

National Institue of Child Wellness and Human Development. (n.d.). Prophylactic to Sleep 2017. Retrieved from https://world wide web.nichd.nih.gov/sts.

-

Function of Affliction Prevention and Health Promotion. (2014). Healthy People 2020: Maternal, infant and child health. Retrieved 31 May 2017, from https://world wide web.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/maternal-baby-and-child-health/objectives.

-

Olds, D. L., Henderson, C. R. Jr., Tatelbaum, R., & Chamberlin, R. (1986). Improving the delivery of prenatal care and outcomes of pregnancy: A randomized trial of nurse home visitation. Pediatrics, 77(1), xvi–28.

-

Parents as Teachers. (2018). Retrieved May 28, 2018, from https://parentsasteachers.org/.

-

Patient Protection and Affordable Care Human action 42 United states of americaC. § 18001 et seq.(2010).

-

Paulsell, D., Avellar, Due south., Martin, S., E., & Del Grosso, P. (2010). Home visiting evidence of effectiveness review: Executive Summary. Washington, DC: Role of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.South. Section of Health and Human Services.

-

Radloff, 50. (1977). The CES-D Calibration: A cocky-written report depression calibration for research in the general population. Journal of Applied Psychological Measure, 1, 385–401.

-

Rozga, M. R., Kerver, J. M., & Olson, B. H. (2015). Self-reported reasons for breastfeeding cessation among low-income women enrolled in a peer counseling breastfeeding support program. Journal of Man Lactation, 31(ane), 129–137.

-

Stuebe, A. (2009). The risks of non breastfeeding for mothers and infants. Reviews in Obstetrics & Gynecology, two(4), 222–231.

-

Job Forcefulness on Sudden Baby Death Syndrome. (2016). SIDS and other sleep-related infant deaths: Updated 2016 recommendations for a safe infant sleeping environment. Pediatrics, 138(5), e20162938. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-2938.

-

Thompson, D. K., Clark, G. J., Howland, L. C., & Mueller, M.-R. (2011). The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Human action of 2010 (PL 111–148): An analysis of maternal-child health home visitation. Policy Politics Nursing Practise, 12(3), 175–185.

-

Wardlaw, T. 1000. (Ed.). (2004). Low birthweight: Land, regional and global estimates. New York: UNICEF.

-

Wen, 50. Thousand., Baur, 50. A., Simpson, J. M., Rissel, C., & Flood, 5. Chiliad. (2011). Effectiveness of an early on intervention on infant feeding practices and "breadbasket fourth dimension": A randomized controlled trial. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 165(eight), 701–707.

-

Williams, C. M., Cprek, S., Asaolu, I., English language, B., Jewell, T., Smith, Chiliad., & Robl, J. (2017). Kentucky wellness admission nurturing development services habitation visiting programme improves maternal and child health. Maternal and Child Wellness Journal, 21(five), 1166–1174.

Acknowledgements

This projection was funded by award D89MC23146 from the MIECHV competitive grant plan from the Health Resources and Services Assistants (HRSA) to the State of Illinois Department of Human being Services (IDHS). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibleness of the authors and do non stand for the official views of HRSA or IDHS. The authors would like to thank their partners at the Ounce of Prevention Fund, the Illinois Governor'due south Office of Early Childhood Evolution, and the agencies that implemented the doula home visiting and example management interventions. The authors thank projection director, Linda Henson, data base of operations manager, Marianne Brennan, and the inquiry staff involved in collecting the data, including Tanya Auguste, Melissa Beckford, Ikesha Cain, Adriana Cintron, Nicole Dosie-Dark-brown, Tytannie Harris, Morgan Johnson-Doyle, Katarina Klakus, Natasha Malone, Jasmine Nash, Erika Oslakovic, Jillian Otto, Amy Pinkston, Magdalena Rivota, Rosa Sida-Nanez, Luz Silva, Caroline Taromino, Ardine Tennial, Maria Torres, Yadira Vieyra, and Lauren Wilder.

Author data

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of involvement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of involvement.

Additional information

The original version of this commodity was revised due to a retrospective Open Access social club.

Rights and permissions

Open Admission This commodity is distributed under the terms of the Artistic Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted apply, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you requite appropriate credit to the original author(south) and the source, provide a link to the Artistic Eatables license, and indicate if changes were made.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this commodity

Hans, S.L., Edwards, R.C. & Zhang, Y. Randomized Controlled Trial of Doula-Home-Visiting Services: Touch on on Maternal and Infant Health. Matern Child Health J 22, 105–113 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-018-2537-7

-

Published:

-

Result Date:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-018-2537-vii

Keywords

- Doula

- Domicile visiting

- Breastfeeding

- Safe slumber

Source: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10995-018-2537-7

0 Response to "2013 Study Foudn That Doulas Were Less Likely to Deliver Babies With Low Birth Weight"

Post a Comment